Astronomical observations laid in the foundation of the life of society of Ancient Egypt, defining the time of agricultural works and religious ceremonies. They became the basis for the shaping of a calendar system of 365 days with three seasons: flood (inundation), sowing (emergence), and harvest. The year was divided into 12 months, each of which contained three 10-days weeks (Decans); it formed 360 days, to which 5 more days (a half week) were added. Egyptians were the first ones who, in the mid-second mil. BCE, started to divide 24-hours period into 12 day hours and 12 night ones. They knew at least five planets (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn) and 43 constellations, which got their names: Nakht (Giant), Reret (She-Hippo), Sah (our Orion), Meskhetyu (Ox‘s Leg, or Adz, our Ursa Major), and others. Egyptians knew the retrograde movement of the Mars, the periods of rotation of the Mercury and the Venus around the Sun.

The main sources on the Egyptian astronomy originate from temples and funeral monuments. The interest to astronomy was in fact inseparable from mythological concepts of Egyptians who deified heavenly bodies. Each temple and tomb were planned and decorated purposefully to reflect heavens, or the abode of gods-luminaries. Many temples were oriented according the East-West axis, which corresponded to the visual way of the Sun across the sky. The floor symbolized earth, the ceiling was an image of heaven. The schedule of temple rites was defined by the activity of the planets: the rising and setting of the Sun and the Moon, the star Sirius, etc.

Heaven was associated with goddess Nut, who, according to myths, swallows the Sun-Ra daily, and delivers him at dawn. Lids of Egyptian sarcophagi, temple and tomb ceilings were often decorated with images of Nut in the form of a female figure outspread on heavens. Aside, there could be scenes of the night and day navigation in the barque of god Ra. The daily travel of the Sun across the night heaven was depicted on the walls of kings’ tombs and it was associated with the motif of resurrection of dead in the afterworld. Those plots laid in the foundation of the so called ‘books of another world’: The Amduat Book, The Gates Book, The Book of Day and Night. The afterworld was divided into 12 regions, in the each of which the Sun has stayed for one night hour. The word ‘hour’ in Egyptian was signed as a star.

The Moon was associated with gods Thoth and Osiris-Iah. The lunar month contained 29 or 30 days. Each day of a lunar month was connected to a certain period of resurrection of dead in another world; it is said in the Pyramid Texts, the Coffin Texts, and in the Book of the Dead. In calendar lists, they accented the new moon, the days of the growing moon, and the full moon, which were taken for the period of passage of a deceased from the earthen world to the afterworld and his or her resurrection for the blessed being.

The mistress of all stars was Sirius (Sopdet, Sotis) — the brightest star of the night sky rising on the eastern horizon short before the flood. The period of invisibility of that star was 70 days; it defined the time for the ritual of mummification and funerals. Sirius was identified with goddess Hathor, Sekhmet, and Isis, the wife of Osiris. Sotis was frequently depicted in the image of a woman staying in a barque, with a star on her head, facing to Osiris, who, in his turn, was connected to the constellation of the Orion’s Belt.

Three planets from five ones known to Egyptians were interpreted as personifications of Horus. Inscriptions of kings’ tombs included images of the Jupiter in the form of a man with a falcon head; he was called ‘Horus connecting Both Earths’, ‘Horus sanctifying Both Earths’, ‘the Southern Star of Heaven’. The Saturn has an image of a man with an oxen head; he was signed as ‘Horus, the ox of heaven’ or ‘Horus-ox’, ‘the Eastern star crossing heaven’. The Mars was imagined as a winged falcon with a snake neck and three snake heads; he was called ‘Horus of the horizon’, ‘Horus the red’, ‘the Eastern star’, and ‘the going backward’. The Mercury was associated with god Seth; he has an image of a falcon with a shake neck and the head of Set h; he was called ‘Seth in the evening twilight, god in the morning twilight’. The Venus was depicted as a two-headed human being or a heron; the name was ‘the Intersecting star’, ‘Phoenix’, ‘Heron’, ‘the Morning Star’.

The main text on Egyptian astronomy was the “Book of Nut’, wich was a collection of Egyptian astronomic texts describing the movement of the Sun, the Moon, the planets, the fixed stars, as well as giving ideas on the sun and water clocks which served for measuring the time. Sun dials (gnomon) were used for the light period and were made of a horizontal basis and a cross bar from which a shadow felt on the basis divided into several sections with notches. In the first half of the day the construction was turned eastward, in the second half — westward.

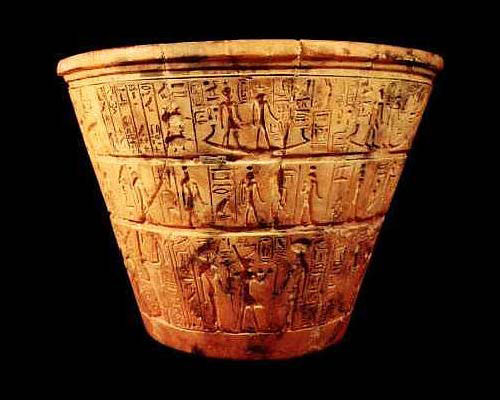

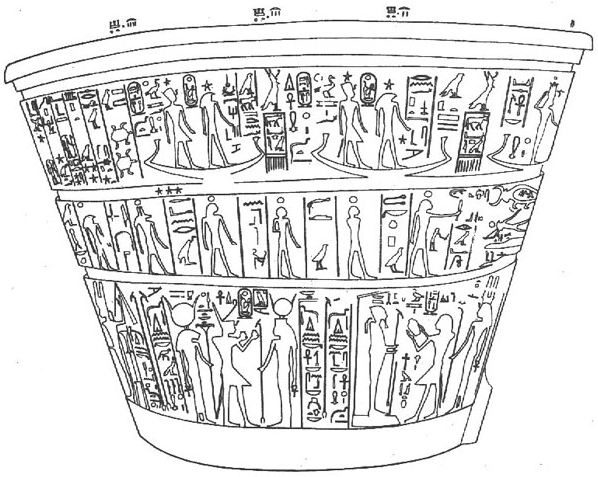

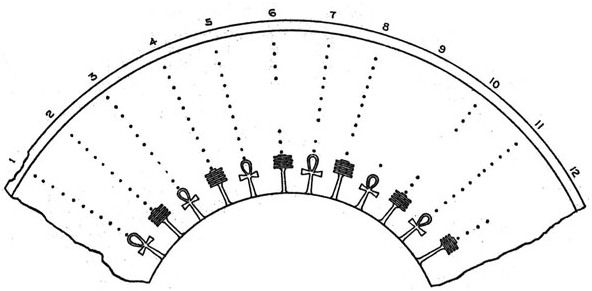

Water clock (clepsydra) was used inside temples in the night period. The inventor of the water clock was a dignitary named Amenemhet (the epoch of Amenhotep I, 16th century BCE); it is said in the inscription in his own tomb (Cotterell, Kamminga 1990, 59–61; Kurtik 1990, 234). Usually, clepsydra had a form of a cup with an opening in its lower part, through which water was flowing out into another vessel. There was a scale with 12 sections on the side of the vessel — each section for a month of the year. They were divided, in turn, into 11 or 12 intervals for night hours.

|

|

| Clepsydra from the temple of Karnak. 14th century BCE. The Cairo Museum (http://www.conec.es/mundo/midiendo-el-tiempo-gota-a-gota-las-clepsidras/) |

|

|

|

| Signs on the inner side of the clepsydra with the months of the year | |

As the star clocks, they used an optical instrument called merkhet (mrxt, literally: ‘instrument of knowledge’); it was a rope plumb line on a wooden bar. Typically, priests-astronomers used two instruments of that type oriented at the Polar Star to find the axis north-south (meridian) in the might sky. For that purpose, two observers set themselves opposite each other — one faced northward, another one southward. They calculated the time on the base of the moment when certain stars or a group of stares, called decans, crossed the meridian. Beside merkhet, they used a kind of theodolite called bay en imy unut — a thin bar with a V-shaped slit in a broader end, through which an astronomer observed stars.

Stars observation in Egypt with the help of ancient theodolite. Reconstruction

Stars observation in Egypt with the help of ancient theodolite. Reconstruction

(www.timetoast.com)

Merkhet. 600 BCE. The Science Museum, London.

Merkhet. 600 BCE. The Science Museum, London.

(www.collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk)

Egyptians classified stars at the ‘imperishable’ (ixmw-skiw), or stars, located in the northern sky; and ‘unwearying’ (ixmw-wrD), i.e. stars of the southern sky. Among the stars there were 36 decans (stars rising with 10-days intervals, together with the Sun), which served for calculating the night time. The decans shape a belt in heaven, different from the zodiacal one; they rise one after another on the horizon every 24 hours. The idea of ecliptic (a year-long way of the Sun in comparison to the stars, as it is visible from the Earth) was, perhaps, included into a myth on the lunar god Thoth, healing an eye of the solar god Horus after his battle against Seth.

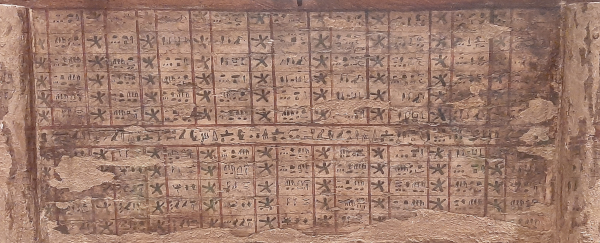

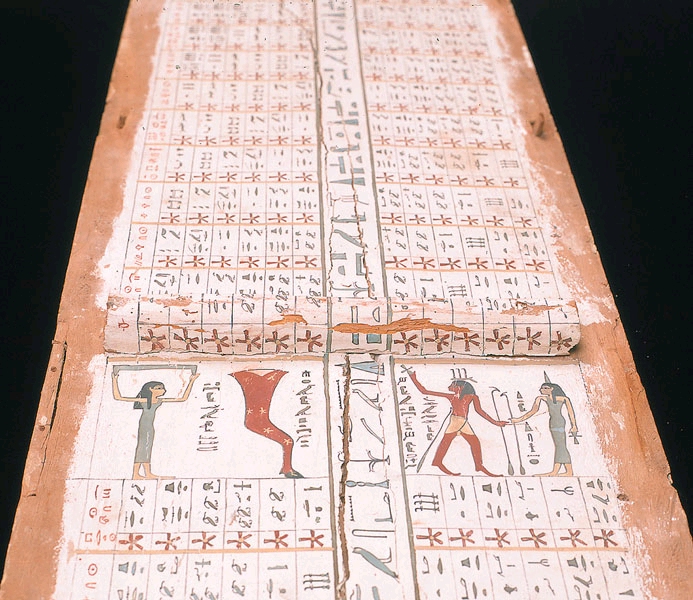

Observations of the mutual disposition of the stars in the each hour of the night, all the year round, were inscribed into tables, which are found on lids of sarcophagi. Columns of those tables reflected a complete annual circle with 10-days intervals. Such calendars allowed a deceased to find his or her way in the afterworld and to calculate the night time and a calendar date. There are 27 known star tables, since the period of the 9th dynasty. They are called diagonal star clocks or diagonal calendars; they contain names of the stars associated with a certain decan. Calendars were divided into bays with horizontal and vertical lines. Horizontal lines contained citations from religious texts with rules of offerings to gods. In the vertical lines, there were images of four gods. Each column with a star name (often highlighted with red) included 12 lines, divided into cells indicating rising (or, possibly, setting) of a certain star on the horizon.

‘Diagonal star calendar’. Depiction on the lid of the sarcophagus of It-Ib from Asyut. 11th dyn. The Roemer and Pelizaeus Museum, Hildesheim

‘Diagonal star calendar’. Depiction on the lid of the sarcophagus of It-Ib from Asyut. 11th dyn. The Roemer and Pelizaeus Museum, Hildesheim

(https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Digaonalsternuhr2.jpg)

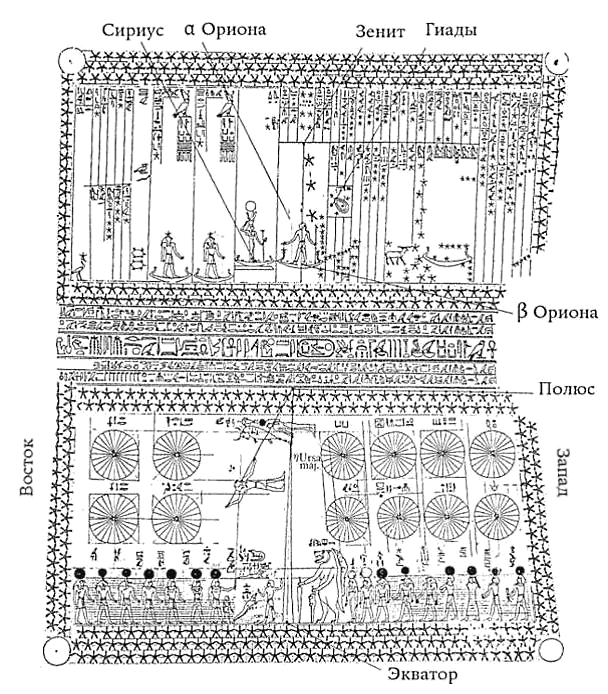

Star maps were located mainly on the ceiling of temples and kings’ tombs (Seti I, Ramesses II, VI, VII, IX). The earliest example of such map was found in Thebes, in the tomb of Senmut (ТТ 353), a dignitary of Queen Hatshepsut (15th century BCE). The astronomical ceiling of that tomb is divided into two parts: the upper one manifests the southern side of heaven, the lower one — the northern side. In the southern side, marking the night hours, there are columns for stars-decans and constellations of the southern hemisphere, such as Orion and Canis Major. There are also the planets — Saturn, Jupiter, Mercury, Venus — in the shape of gods navigating heaven in barques. Mars is presented as an empty barque in the western part of the scheme. The whole scene fixes a specific event: a connection of planets at the same longitude with Sirius; it allows specialists to date this event at 1534 BCE (van Spaeth 2000). The empty boat probably marks the retrograde motion of Maars, which was in the west at that time, separate from other planets.

In the centre of the northern part, there are constellations of the northern hemisphere, including Ursus Major and Ursus Minor. On the left and on the right, there are, correspondingly, four and eight circles; under them, there are gods with a solar disc on their heads; they are walking to the centre of the composition. According the inscriptions, the circles mean festivals of the lunar calendar, and gods — days of the lunar month.

The astronomical ceiling in the tomb of Senmut (ТТ 353; Thebes).15th century BCE (drawing)(Nort 2020, fig. 18).

The astronomical ceiling in the tomb of Senmut (ТТ 353; Thebes).15th century BCE (drawing)(Nort 2020, fig. 18).

Astronomical observations of Egyptians were provoked by the necessity to find the favorable time for starting sowing and harvesting, for foretelling the beginning of inundations and hunger. Besides, they believe that god-planet can influence the life of the society and a single man. That is why it was necessary to perform rituals for the sake of those gods, for their appeasing. In the inscriptions of the Greek-Roman time in the temple of Edfu, for instance, there are such words about the star Sirius (Sotis): “I am Sotis… ruler of the arrow… [plotting] against her are to die, when she is inflaming, she is like a woe of the year (= epidemy?), which brings bad luck (sent) by Sekhmet” (Goyon 2006, 116). Thus, goddess Sotis was associated with the lion goddess Sekhmet characterized with ferocious disposition and able to bring both calamities such as drought and favorable flood. In the New Year day, coincided in time with the festival day of rising Sirius, they perform the ritual of ‘appeasing Sekhmet’ for the sake of pacifying the temper of the goddess and getting her protection.

Such system of interconnection of the cosmos and human activity conditionally can be called ‘astrology’, which has been linked with the practice of fortune telling for a long time. Astrological horoscopes appeared not earlier than Egypt was conquered by Assyrians (670 BCE). According the note by Latin writer and astrologer Julius Firmicus Maternus (4th century CE), the system of horoscopic astrology was transferred to ruler Nekauba/Nechepsos (7th century BCE) and his priest Petosiris. In the Greek-Roman period, the concept of 12 signs of zodiac was shaped in Egypt; it was got by Greeks from Babylonian astronomy. The earliest Egyptian zodiacs are dated to the Ptolemaic rule, to the first century BCE — they were found in the temple of Dendera.

The zodiac from the Dendera temple (drawing) (Aubourg 1995, p. 4, fig. 2)

The zodiac from the Dendera temple (drawing) (Aubourg 1995, p. 4, fig. 2)

Bibliography

- Kurtik G. E. Astronomiya Drevnego Egipta (Astronomy of Ancient Egypt) // Na rubezhakj poznaniya Vselennoi (IAI XXII). Moscow: Nauka, 1991. P. 207–265.

- Nort G. Cosmos: Illiustrirovannaya istotiya astronomii i cosmologii (Illustrated history of astronomy and cosmology) / transl. From English. Moscow: NLO, 2020.

- Aubourg É. La date de conception du zodiaque du temple d’Hathor à Dendera // 1995. Vol. 95. P. 1–10.

- Clagett M. Ancient Egyptian Science. Vol. II: Calendars, Clocks, and Astronomy. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1995. URL: https://books.google.ru/books?id=xKKPUpDOTKAC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Ancient+Egyptian+Science&hl=ru&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiCm4a9_KvqAhVB0aYKHUQ1AgQQ6wEwAXoECAUQAQ#v=onepage&q=Ancient%20Egyptian%20Science&f=false

- Cotterell B., Kamminga J. Mechanics of pre-industrial technology: an introduction to the mechanics of ancient and traditional material culture. N.-Y.: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1990.

- Goyon J.–C. Le rituel du sHtp %xmt au changement de cycle annuel. D’aprés les architraves du temple d’Edfou et texts paralléles, du Nouvel Empire à l’époque ptolémaque et romain. Le Caire, 2006 (BdÉ, 141).

- Leitz C. Studien zur ägyptischen Astronomie. Wiesbaden, 1989 (Ägyptische Abhandlungen, vol. 49).

- Neugebauer O., Parker R.A. Egyptian Astronomical Texts. 3 vols. Providence, RI: Brown Univ. pr., 1960–1969.

- Quack J.F. The Planets in Ancient Egypt // Oxford research encyclopedias. 2019. P. 1–32 [Electronic Source]. URL: https://oxfordre.com/planetaryscience/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190647926.001.0001/acrefore-9780190647926-e-61?print=pdf (access: 2.07.2020)

- van Spaeth O. Dating the oldest Egyptian Star Map // Centaurus. 2000. Vol. 42. P. 159–179.

- von Lieven A. Astronomical ceilings, Egypt // The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. Wiley Online Library. URL: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah21052 (дата обращения: 2.07.2020)

Sources

|

Hours |

Publication |

| List with indication of the duration of day and night in the Cairo Calendar 86637, C Verso XIV (12th century BCE; Cairo Museum) | Bakir A. el-M. The Cairo Calendar no. 86637. Cairo, 1966 |

| Water clock from the epoch of Amenhotep III from the Karnak temple of Amon-Ra (15th–14th centuries BCE; Cairo Museum) |

Clagett 1995, fig. III. 21a |

| Water clock from the Late Time (664–30 BCE; Metropolitan Museum) |

Clagett 1995, fig. III.32 Photo on the site of the Metropolitan Museum: |

| Water clock from the epoch of Philip Arrhidaeus (4th century BCE; British Museum (cat. no. 938) |

Clagett 1995, fig. III. 21b Photo on the site of the British Museum: |

| Water clock from the epoch of Philip Arrhidaeus (4th century BCE;. British Museum (cat. no. 948) |

Clagett 1995, fig. III. 21d Budge E.A.W. A Guide to the Egyptian Galleries (Sculpture), British Museum. L., 1909. Cat. no. 948. Photo on the site of the British Museum: |

| Diagonal calendars | |

| Coffins of Mesakhiti, Mait, Khiti, pseudo-Nakhiti, Hunnu, Thephabi from Asyut (IX–X dyn.) |

Pogo A. Calendars on Coffin Lids from Asyut (Second Half of the Third Millennium // Isis. 1932. Vol. 17, No. 1. P. 6–24. |

| Coffin of It-Ib (It-ib) (XI dyn.) |

Neugebauer, Parker 1960, vol. I, pl. 3–4. Clagett 1995, fig. III.16 |

|

Coffin of Idy (Idy) from Asyut (? Dyn.) |

Neugebauer, Parker 1960, vol. I, pl. 5–6. Clagett 1995, fig. III.14 |

| Coffin of Mereru (Mrrw) from Asyut (XII dyn.; Museum of Torino) |

Detoma E. On two star tables on the lids of two coffins in the Egyptian Museum of Turin // Atti Sc. Mor. 2014. Vol. 148. P. 134–135 (URL: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328342944 (access: 2.07.2020)

|

| Astronomical ceiling | Publication |

| The tomb of Senmut (ТТ 353) in Deir el Bakhri (15th century BCE) |

Pogo A. The Astronomical Ceiling-Decoration in the Tomb of Senmut (XVIIIth Dynasty) // Isis. 1930. Vol. 14, No. 2. P. 301–325; Drawing and English translation: Clagett 1995, 221–230, fig. III.4. Facsimile on the site of the Metropolitan Museum: |

| The tomb of Seti I (KV 17) (13th century BCE) |

PM I-2², 542 (41); LD III, Bl. 137 (http://edoc3.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/lepsius/tafelwa3.html) Hornung E. The Tomb of Pharaoh Seti I. Zurich, Munich, 1991. English translation: Clagett 1995, 239–249. Photos and drawings in the database of the Theban Mapping Project: https://thebanmappingproject.com/tombs/kv-17-sety-i |

| The tomb of Ramesses V and Ramesses VI (KV 9) (12th century BCE) |

PM I-2², 511 (3), 512 (7, 11), 513 (14), 514, 517; Piankoff A., Rambova N. The Tomb of Ramesses VI. 2 vols (Bollingen Ser., XL). N.-Y., 1954. Pls. 142–144, p. 384, pls. 146–159, p. 384–428, pls. 186–196, p. 398, 415, 421. Photos in the database of the Theban Mapping Project: https://web.archive.org/web/20101130081121/http://thebanmappingproject.com/sites/browse_tomb_823.html Virtual tour inside the tomb: https://describingegypt.com/tours/ramessesvi/kv9_burial_chamber_j_entrance_east?h=359&v=-71&f=80 |

| The tomb of Ramesses VII (KV 1) (12th century BCE) |

PM I-2², 496 (9–10); Hornung E. Zwei ramessidische Königsgräber. Ramses IV. und Ramses VII. von Zabern, Mainz, 1990. Photos and drawings in the database of the Theban Mapping Project: http://www.thebanmappingproject.com/sites/browse_tomb_815.html |

| The tomb of Ramesses IX (KV 6) (12th century BCE) |

PM I-2², 502; LD III, Bl. 228 (http://edoc3.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/lepsius/tafelwa3.html), LD Text III, p. 199; Guilmant F. Le tombeau de Ramses IX. Cairo, 1907. |

| Ramesseum Temple (13th century BCE) |

Medinet Habu. Festival Scenes of Ramses III / Eds. J.A. Wilson, T.G. Allen. Vol. IV (OIP, 51). Chicago, 1940. Pl. 478; Clagett 1995, fig. III.2. |

| Horus Temple in Edfu (2nd century BCE) |

PM VI, 133; Kurth D. Treffpunkt der Götter: Inschriften aus dem Tempel des Horus von Edfu. Zürich; München, 1994. P. 27. |

| Temple in Dendera (Greek-Roman time) |

PM VI, 49, 58–59; Dendérah IV, 176: 4–178:5, pls. 292–297; Clagett 1995, fig. III. 97. Transliteration and translation: Cauville 2001, 284–287. |

|

Isis Temple on Philae Island (Greek-Roman time) |

PM VI, 237; LD IV, Bl. 35b (http://edoc3.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/lepsius/tafelwa4.html) |

| Deir el-Haggar Temple (2nd century CE) |

Kaper O. The Astronomical Ceiling of Deir el-Haggar in the Dakhleh Oasis // The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 1995. Vol. 81. Fig. 1. |

| Book of Nut | Publication |

| Cenotaph of Seti I in Ossireion in Abydos (13th century BCE) |

PM VI, 30; Frankfort H. The Cenotaph of Seti I at Abydos. L., 1933 (Egypt Exploration Society). Vol. II. Pl. 81; Clagett 1995, fig. III. 95а–b, 98 a–b; p. 371–383, 399–401 (English transl.) |

| Tom of Ramesses IV (KV 2) (12th century BCE) |

PM I-2², 500 (15); Neugebauer, Parker, Astronomical Texts, vol. 1, pls. 34 – 35, 44–51; Lefébure E. Les hypogées royaux de Thèbes. Bd. 3: Tombeau de Ramses IV. P., 1889. Pl. XXVII; Hornung E. Zwei ramessidische Königsgräber. Ramses IV. und Ramses VII. von Zabern, Mainz, 1990. S. 89–96; Clagett 1995, fig. III. 96b. Photos and drawings in the database of the Theban Mapping Project: https://web.archive.org/web/20101130082810/http://thebanmappingproject.com/sites/browse_tomb_816.html |

| Tomb of Mutirdis (ТТ 410) (26 dyn.) |

Assmann J. Das Grab der Mutirdis. von Zabern, Mainz 1977. S. 85–88. |

| Carlsberg Papyrus I (2nd century CE) |

Lange H.-O. Neugebauer O. Papyrus Carlsberg No. 1 – Ein hieratisch-demotischer kosmologischer Text. Munksgaard, Kopenhagen, 1940; The Carlsberg Papyri 1: Demotic Texts from the Collection / Ed. P. J. Frandsen. URL: https://pcarlsberg.ku.dk/publications/. |

|

Zodiacal constellations |

Publication |

| Zodiacs in the Hathor Temple in Dendera (Greek-Roman time) |

Lauth F.J. Les zodiaques de Denderah. Mémoire où l'on établit que ce sont des calendriers commémoratifs de l'époque gréco-romaine. Munich, 1865; Clagett 1995, fig. III. 76a–с; p. 471–484 (описание) Round zodiac in the base of the Louvre collections: http://cartelen.louvre.fr/cartelen/visite?srv=car_not_frame&idNotice=19044

|

| Khnum Temple in Esna (Greek-Roman time) |

PM VI, 116; Clagett 1995, fig. III. 75 a–c, 102; p. 471–484 (description) Hemeda S. Reconstruction of the first zodiac: Esna A // The First International Conference on Egypt and Mediterranean through Ages at Cairo University, Egypt (October 2014). URL: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322557627_Reconstruction_of_the_first_zodiac_Esna_A (date of call: 2.07.2020) |

| Zodiacs from the tomb of Petosiris (54–84 CE) |

Neugebauer O., Parker R.A., Pingree D. The Zodiac Ceilings of Petosiris and Petubastis // Osing J. Et al. Denkmäler der Oase Dachla aus dem Nachlass von Ahmed Fakhry. Mainz am Rhein, 1982. P. 96–101; Clagett 1995, fig. III.100 a, III.100b |

| Zodiac from the tomb of Petubastis (Roman time) |

Neugebauer O., Parker R.A., Pingree D. The Zodiac Ceilings of Petosiris and Petubastis // Osing J. Et al. Denkmäler der Oase Dachla aus dem Nachlass von Ahmed Fakhry. Mainz am Rhein, 1982. P. 96–101; Clagett 1995, fig. III.101 |

| Two horoscopes and zodiacs from the tomb of two brothers in Atribis (2nd century CE) |

Petrie W.M. Athribis. L., 1908. P. 12, pl. XXXVI. URL: http://www.etana.org/sites/default/files/coretexts/15110.pdf Clagett 1995, fig. III.104 |

Tags: Ancient Egypt, Alexandra V. Mironova, Articles, Astrology

English (United Kingdom)

English (United Kingdom)  Russian (Russia)

Russian (Russia)