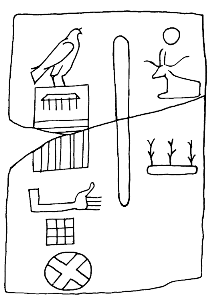

Shaping of the calendar system in Egypt took place as early as in the Predynastic period. It is clear from an ivory palette dated to the time of the I dynasty: with depictions of the cow (Isis-Sotis), solar signs, and signs of the year (rnpt) the Nile inundation (Axt). According to R. Parker, the phrase is read: “Sotis, opener of the year, the Nile inundation” (Parker 1950, 34). This inscription testifies that Egyptians saw a connection between the beginning of the Nile flood and the heliacal rising of the Sirius (Egypt. Sopdet, Greek Sotis) even before the state has been formed.

Ivory palette (I dynasty) (Parker 1950, p. 34)

Ivory palette (I dynasty) (Parker 1950, p. 34)

Nevertheless, Russian Egyptologist O.D. Berlev, on the base of his studying an inscription from a stela from the Sehel Island and a text by Greek author Elian, came to the conclusion, that the calendar system of 365 days was established not earlier that in the epoch King Djoser (III dyn.), exactly, in the 18th year of his reign (on Berlev, c. 2767 BCE). It was then, according to the researcher, Egyptians caught a connection between the rising of the Sirius and the flood (Berlev 1999, 9–10). However, firstly, it is difficult to imagine that people living in an agrarian country for many generations had not mention such connection. Secondly, inscriptions of the Palermo Stone show that, since the I dynasty, Egyptians had kept track of years of each reign, celebrated festivals, and observed the level of the Nile. Therefore, by the moment of the foundation of the unified state, there was a calendar system in Egypt, which included festivals of certain periodicity. Most likely, there was an unseen event under Djoser: the rising Sirius brough not the Nile inundation, as usual, but a catastrophic draught seven years long. That is why they established festivities for gods of the Upper Nile flood — and Khnum was one of them.

The calendar system of Ancient Egypt was connected to the cycle of the Nile floods and consisted of three seasons: inundation, sowing, and harvesting (Axt, prt, Smw correspondingly); each of them included four months of 30 days each. The season of inundation was in September-January, the season of sowing or ‘seedlings’ — in January-May, the season of harvesting or ‘low water’ — in May-September. Egyptians added five more days to such 12 months, getting a 365-day long calendar year approximately equal to the solar year. Such calendar is basically called ‘civil’ one (civil year). Beside it, Egyptians used a lunar calendar with 12 month also, but their duration varied depending in the length of a full lunar cycle (usually 29 or 30 days). Every lunar month was started with the new moon and was called on the main festival of that month. Because the lunar calendar was 10 or 11 days shorter the solar one, once in two or three year, they added the 13th (wandering) month of thoth to accommodate the lunar calendar to the solar cycle. Such procedure is known as intercalation. The beginning of the calendar lunar year was linked to the heliacal rising of the star Sirius (Sotis), observed on the eastern horizon before the sunrise in the middle of summer (approximately July 17). The time of coming the star determined a necessity to add the month of thoth.

The civil calendar, which was shaped, evidently, later than the lunar one, did not depend on the rising Sirius, although it was based on the system of the lunar cycle; it was manifested in the division of the year into three seasons and in the names of the months transferred from the lunar calendar. Because of the lack of the lip year in the Egyptian civil calendar, every three or four years the calendar New Year lagged one day behind the solar of the Sirius (Sotis) year. In 1460 years (the so called the Sotis cycle), such difference summed up till its ‘disappearance’ — the rising of the Sirius came to the solar New Year day again; thus, the beginning of the civil and solar years coincided. In the fourth century BCE, they built a schematic 25-years long lunar calendar on the base of the civil one; it allowed them to calculate the beginning of the lunar months without practical observations for the lunar phases.

| No | Seasons’ names | Ancient form | New Kingdom | Greek-Roman time |

|

I |

Axt |

txy |

+Hwt(y) |

Thoth |

|

II |

mnxt |

pA-n-Ip(A)t |

Phaophi | |

|

III |

@tHr |

@tHr |

Athyr | |

|

IV |

NHb-kAw |

kA-Hr-kA |

Khoiak | |

|

V |

prt |

Sf-bdt |

tA abt |

Yibi |

|

VI |

rkH wr |

(pA-n-)mxr |

Mechir | |

|

VII |

rkH nDs |

pA-n-ImnHtp |

Phamenoth | |

|

VIII |

Rnnwtt |

pA-n-Rnwtt |

Pharmuthi | |

|

IX |

Smw |

#nsw |

pA-n-#nsw |

Pakhon |

|

X |

#nt-Xt(y) |

pA-n-int |

Payni | |

|

XI |

Ipt Hmt |

Ipip |

Epifi | |

|

XII |

wp(t)-rnpt |

(mswt-)Ra-@rAxty |

Mesore |

Bibliography

-

Berlev O.D. Dva perioda Sotis mezhdy godom 18 kingya Senu ili Tosortrosa i godov 2 pharaona Antoniya Piya (Two periods of Sotis between the year 18 of King Senu or Tosortros) // Drevnyi Egypet. Yazyk, kultura, soznanie / edit. O.I. Pavlov. Moscow: Oriental Studies Institute, 1999. P. 42–62.

-

El-Sabban S. Temple Festival Calendars of Ancient Egypt. Liverpool, 2000.

-

Parker R. A. The Calendars of Ancient Egypt. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago pr., 1950 (SAOC, 26).

-

Spalinger A. Feasts and Fights: Essays on Time in Ancient Egypt. New Haven: Yale Egyptological Institute, 2018.

Tags: Ancient Egypt, Alexandra V. Mironova, Articles, Time terms

English (United Kingdom)

English (United Kingdom)  Russian (Russia)

Russian (Russia)